Context and Methods

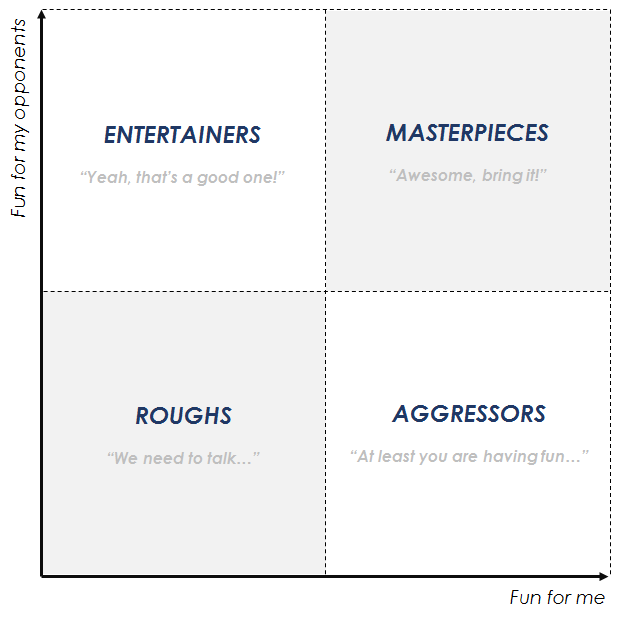

Back in February I wrote a proposal on how to use Gartner’s Magic Quadrant to map out a player’s Commander decks. The goal was to identify the links between one person’s fun and the appreciation the rest of the playgroup had for certain decks.

While the initial approach was but an interesting first take on the subject, most of the analysis was envisioned as a single-player perspective, with the idea of understanding if certain patterns could be identified. One thing that quickly jumped to mind was the possibility to enrich this analysis with a larger sample size.

Instead of just focusing on a single player, I wanted to see if the principle could be applied to an entire playgroup and what could be derived from such an analysis. The Commander Magic Quadrant (CMQ), after all, is envisioned as a resource for measurement of fun among members of a playgroup, so it just felt natural to build on this idea and see how many additional perspectives could be collected.

I was fortunate enough to recruit seven volunteers from my own playgroup and we organized a two-step evaluation, building on the principles of the original CMQ:

- First, each player ranked their decks in terms of personal enjoyment

- Then, each player ranked everyone else’s deck based on perceived fun when playing against them; since we had access to 40 decks, each player assigned a score of 40 to their favourite deck and proceeded with a descending ranking; quite intuitively, players voted for all decks but their own and the ones they did not have a chance to play against

With no way to quantify fun through a universal management, the two steps were translated into a ranking system along two axes:

- Personal enjoyment dictated the horizontal distribution of decks; since not all players had an equal roster of Commander decks, we simply agreed on a linear distribution, with equidistant decks along the X axis for each player

- Average scores of other players’ decks formed a single vertical ranking; since the 40-to-0 ranking was largely arbitrary, we distributed the decks, again with equidistant decks along the Y axis

To theorize players’ profiles and see if any pattern was perceivable, we kept track of deck’s ownership with a single letter per player. In the following paragraphs, I will be referring to the members of our playgroup, myself included, with the assigned letters.

The result of this analysis is summarized in the following CMQ.

Having access to eight players and forty decks, the result is quite dense and, on first glance, chaotic. Fortunately enough, we soon identified some interesting phenomena in the decks’ distribution.

A playgroup’s CMQ Areas

First and foremost, six out of the eight players had their personal favourite deck in the top right corner. Not only that, but two players actually had two decks and one player had three. All these decks were scoring high both in terms of personal enjoyment and playgroup’s appreciation.

Knowing both the players and the decks’ positioning, it became evident that these decks hold a special role in our own metagame, as each of these serves the implicit purpose of being the signature deck of the player. I will start with the two most interesting ones, though each of them presents a very notable case study:

- B is probably the most political player in our playgroup; he thrives in negotiations and he often takes a defensive stance within games; his non-aggressive nature means that he is rarely perceived as carrier of a negative experience for the group, hence three of his five decks ranked in the Masterpiece area

- F plays Black every time he can and both his Masterpiece decks feature a very strong Black component: his Xiahou Dun, the One Eyed deck is all about Graveyard recursion, while his Scarab God deck goes all in on the reanimation strategy; this deckbuilding practice is how he approaches almost every aspect of Magic, so it would really come as a surprise to see him pilot a Naya deck of sort

It is interesting to note how these signature decks seem to be separated by all the others, with an implicit line parting these beloved decks from the rest of the bunch.

The bottom quadrants of the CMQ, and especially the Aggressor area, feature a number of very powerful and very disliked decks. As the name suggests, each of these decks is infused with a strongly proactive strategy, either in the form of reliable and non-interactive beatdown decks, or dedicated combo decks.

Here we have R’s Kozilek, Butcher of Truth deck and G’s Ulamog, the Infinite Gyre deck, R’s Saskia, the Unyielding Infect deck and M’s Rashmi, Eternities Crafter combo deck, which is all about generating infinite Mana with Deadeye Navigator and Palinchron.

While strategies here may vary quite significantly, the common denominators are the usage of non-political strategies, the resilience to countermeasures and the usage of destructive methods that rarely lend themselves to interactive games. Much like the signature decks, these aggressive decks also appear to be separated from the rest of the sample by an empty zone, where we can trace a potential border.

The mid sections of the CMQ include a number of different decks. The left portion seems to feature many non-oppressive decks, most of which do not feature combos or non-interactive strategies. These decks tend to be moderately appreciated, thanks to their relative openness to interactive and political games. On the other hand, they bear very little resemblance to the players’ signature decks, often ending up as the polar opposite of what each player really loves doing.

If M is renown in the playgroup for his creative, powerful and explosive builds, his Bruse Tarl, Boorish Herder / Tymna, the Weaver Aggro deck runs the risk of feeling too linear and straightforward. If C is known to be a value-oriented player, helming a consistent and reliable Glissa, the Traitor deck and often indulging in Artifact-based strategies, his Jori En, Ruin Diver deck suffers from the lack of a similarly consistent engine and it is nowhere near the explosive potential of his Mayael, the Anima deck.

Outside of this zone of decks feeling atypical for the players helming them, we meet a sort of “neutral zone”. These decks are not radical enough to fall under any of the identified areas and end up in the middle of the CMQ, bearing characteristics of some areas, but without fully embracing them. Here we find G’s Emmara, Soul of the Accord deck, part Aggro deck, part Combo deck. Not far from that we meet M’s Avacyn, Angel of Hope deck, which falls in the middle of the vertical axis due to very mixed receptions from the playgroup.

The best players

If Commander is all about the overall level of fun shared among players, a first approach to a playgroup can be taken by looking at the player with the highest average scores among all their decks.

I already mentioned how B is among the most political players in our playgroup and how C is renowned for his non-oppressive value-based decks. What is interesting is that, despite having very different playstyles and preferred colour combinations, they display very similar patterns in their decks’ preferences and reception.

B truly embodies the concept of White-Blue decks, bringing an implicit idea of fairness and justice in all his decks. If you take into consideration the fact that nowadays he rarely plays his Edgar Markov deck, all his other decks fair above average and most of them feature very similar colour combinations. If Rakdos is the colour combination of lust, violence and brutality, he is as far from that as one can be, often preferring reactive strategies to oppressive builds. A true testament to his political prowess comes with the fact that the two most appreciated decks of the entire playgroup belong to him.

A very different approach is what drives C in his deckbuilding efforts. We occasionally joke about how his three preferred decks, Glissa the Traitor, Mayael, the Anima and Saheeli, the Gifted follow a similar play pattern of establishing a small board presence in the early game, only to surprise the playgroup with a large, often colourless threat. The lack of oppressive combos and game locks makes sure that, despite these explosive plays, he is rarely perceived as a hardcore Spike, according to Magic’s personality traits.

The Spikes and the Johnny

Speaking of Spikes, M, P and, to a lesser extent, V display a similar distribution to the Spike Curve theorized in the first article on the CMQ. Aside for one exception, each of these players seem to prefer decks that tend to be less liked by the rest of the playgroup, while they tend to appreciate much less the decks that are more thoroughly enjoyed by the rest of players.

While this is nothing to be blamed for, their rankings appear to simply be a manifestation of their Spike tendencies. When personal enjoyment is skewed ever so slightly in favour of victory, the result is an inverse correlation between opponents’ enjoyment and personal accomplishment.

P appears to be the most constant player in this, as his descending trend is almost perfectly linear, with just a small ascending bit on his Ezuri, Claw of Progress deck. Ironically, P is also the most erratic member of the playgroup, sometimes sacrificing deck consistency or in-game politics in the name of personal enjoyment. The results are strategies that veer between the hyper aggressive and the weird build-around.

M, on the other hand, displays a more varied take, with fluctuating trends and a significant peak in his Jodah, Archmage Eternal deck. Among the entire playgroup, he is the one who mostly enjoys playing around and breaking the rules of the format. Rarely does he play a linear and aggressive deck, opting instead for cheating Mana costs with Jodah, Archmage Eternal, destroying the entirety of his opponents’ boards with Avacyn, Angel of Hope, or playing off his opponents’ hand with Sen Triplets. This is where his Johnny nature emerges the most, as he is not interested in simply winning a game with a non-interactive combo. He wants to break the implicit rules of the game, to win with something he perceives as his own creation.

V displays a similar descending trend, although the fact that he only currently plays two different decks strongly limits the number of trends that can be theorized.

Nevertheless, the common factor of these three players is that their decks largely end up being perceived as quite aggressive and imposing, at the cost of the playgroup’s fun. Therefore, the majority of their decks fall below the playgroup’s average.

The twins

The truly unexpected finding was the similarity between two players’ patterns. Before going in the details, I’d like to preface the graph with some notable elements:

- Both players currently own eight Commander decks: one colourless deck, two mono-coloured deck, three two-colour decks, one four-colour deck and one five-colour deck

- Both players built an Eldrazi-centred deck, which is among the least-enjoyed decks within the rest of the playgroup

- Their signature decks are both two-colour decks; both are strongly Commander-centric, as the entire deck is built around the Legendary Creature at the helm

- Their second favourite decks are also strongly Commander-centric and they both feature a relatively low Creature count

- Despite a very different composition, their third favourite decks are both Tribal or mostly Tribal; both these decks are relatively disliked by the playgroup; the same applies for their seventh favourite deck

- Their fourth favourite decks are exclusively or primarily White and Green; both these decks received average scores among the rest of the players

- Their fifth favourite decks are both four-coloured; they are both built around a Commander 2016 Legendary Creature and not a pair of Partners; they are vaguely disliked by the playgroup, due to their usage of hardly interactive strategies

- Their sixth favourite decks are two-coloured; these share similarities to their signature decks, with an overlap of one of the respective colours; these decks are fairly appreciated by the playgroup

- Their least favourite decks are both mono-Red; these two mono-Red decks are both chaotic in nature and not necessarily competitive

Oddly enough, the two players tend to have a fairly different playstyle, with G preferring proactive strategies and R often approaching games with a more reactive behaviour. During games, G usually likes to be perceived as a potential game-breaking threat, holding the table hostage under the promise of an incoming, usually Infect-based, assault. R, on the other hand, tends to play more conservatively, often holding onto key cards in his hand and manipulating players into exhausting their own resources, instead of being the proactive force propelling a game.

Moreover, their individual evaluations of the playgroup’s decks are rarely similar, proving that they also tend to seek different play experiences from the rest of the playgroup. If one likes aggressive and fast-paced games, the other tends to seek a completely different method of board management.

Nevertheless, their placements on the CMQ are oddly similar.

How this is possible is truly beyond my understanding and I must confess a part of me is sincerely scared. I am currently blaming a mixture of randomness and cross-contamination of the two players, who may have evolved into having similar preferences, despite coming from completely different mindsets and backgrounds.

More data needed

Two players were able to submit only a handful of decks, due to currently having a fairly limited roster of options. One of them, F, is a veteran of the format, having played similar decks for the past few years. The other, V, is a relative newcomer to the playgroup and, although his decks’ placement seem to suggest a Spike trend, his sample size appears to be too small to clearly determine a trend.

It is worth mentioning, however, how F places himself in what really looks like a proto-Tablemate Curve, as we described it before. There seems to in fact be a direct correlation between his enjoyment and the playgroup’s appreciation for his decks. While this is not necessarily due to a complete commitment to the playgroup’s experience as the key aspect of his gaming approach, it is also worth mentioning that he has proven time and time again to be fairly adverse to straight up combo decks, of which his Gitrog Monster deck is a close approximation. And, as a result, it also is the deck he seems to enjoy the least.

It is worth mentioning that F is currently tuning a new Judit, the Scourge Diva deck, so we may be soon adding new data points to this analysis.

Variance

There was one final aspect I wanted to look at, as Kyle Carson gave me an extremely good idea when I first wrote about the CMQ back in February. All these analysis, especially on the vertical axis, have been performed in terms of evaluation of average scores. The higher the average score, the higher the appreciation of a deck within the playgroup.

Averages, however, only paint a part of the full picture. An analysis of the standard deviation associated to each deck could help expanding on the analysis, providing insights on how mixed or polarized a deck’s reception is.

In order to focus solely on consolidated numbers, we looked only at the decks that received five or more votes from the rest of the playgroup. Each of these decks was resized on the CMQ based on its standard deviation, so as to provide a quick overview of the relative variance between receptions of different decks.

First and foremost, it is interesting to note how the standard deviation of some decks drastically overshadows the one for others. R’s Grimgrin, Corpse-Born deck has a standard deviation of 2.16, while M’s Sen Triplets deck scored an impressive 11.21. The decks were evaluated six and five times, respectively. Similarly, B’s Ephara, God of the Polis deck reported a standard deviation of 2.77 among five received votes, while G’s Kumena, Tyrant of Orazca deck recorded a 11.10 standard deviation among six votes.

While listing all the decks would probably be lengthy and not necessarily useful, it is interesting to note how the two players with the largest standard deviations are M and G. Despite the two players having a fairly different profile of decks’ averages, their decks received the most mixed receptions. In fact, the five decks with the highest standard deviations belong to the two of them. On top of Sen Triplets and Kumena, Tyrant of Orazca, the two are responsible for introducing the playgroup to Rashmi, Eternities Crafter, Jodah, Archmage Eternal and Zozu, the Punisher.

The common factor of these two players seems to lie more in their in-game approach: both players are fairly proactive and aggressive in their playstyle, despite their different approach to the very concept of proactiveness. If G is more focused on frontal assaults and displays of power, M prefers a less linear plan, usually exploring routes that do not necessarily take him towards all-out attacks. To put it simply, I don’t think I have ever seen M swing with three different Creatures in a single combat phase, while to G that would probably feel like a fairly unimpressive feat.

A different representation of the decks’ variance comes with the visualization of minimum and maximum scores achieved by each deck. The results are quite interesting, as they highlight how some decks were ranked simultaneously among the top and the bottom by different players.

Among the most interesting examples, the already mentioned Sen Triplets deck piloted by M was ranked at the top by V and at the absolute bottom by G. While it is certainly not the only example of the intrinsically subjective nature or fun and enjoyment, its variance is the most notable in the entire sample.

Conclusions

This analysis was made possible only by the collaboration of all the participating players. I am sure there is a number of additional analyses that could be performed, as well as perspectives to address. Nevertheless, I must confess I feel this is a good batch of results for a first comparative analysis within our playgroup.

Of course, I strongly recommend trying this yourself and see what you can derive from your playgroup’s analysis. Of course, it takes a lot of collaboration and effort, but the results are certainly interesting. And, at worst, you will have a better understanding of what your playgroup likes the most, so you can confidently pick the best deck to take to your local game store.

Before we close, I want to thank all the friends taking part in this effort. You can find some of them on Twitter, in case you want to ask about their decks and play stiles. In strictly alphabetical order: Marco “B”, Marco “C”, Luigi “G”, and Francesco “P” are all on Twitter. And a special shoutout to Kyle Carson for inspiring the standard deviation analysis.