What is a Magic Quadrant and how magical is it?

A Magic Quadrant is a graphical tool introduced by Gartner Inc. to easily communicate the state of the art of a market sector, usually mapping top-trending companies based on their vision and capability of execution. Many leading make their mission to strive for the prized title of Leader, which is only awarded to the companies that can effectively balance an innovative and compelling vision with a practical and tangible execution strategy.

The result is an easily-readable two-by-two matrix, with the Leaders in the top-right corner and the Niche Player in the bottom-left. As Magic Quadrants are periodically re-issued, investors are strongly encouraged to keep an eye on significant movements between one Magic Quadrant and the next. An improvement of a company’s vision or the worsening in its execution capability may lead to significant shifts in the composition of power within a specific market.

I will gladly spare you the details of how Gartner Inc. performs its analyses, how companies are assessed and how much effort is put into what looks like a very simple chart. It’s a very interesting read if you have some hours to spare. What really sells Magic Quadrants, to me, is how incredibly polished and readable the final product is. Just a peak at any Magic Quadrant provides a very synthetic and clear view at an entire market sector, pinpointing true innovators, followers and everything in between.

Magic Quadrants have then been often revisited, and even bastardized, to map more than companies. Products, concepts and even vague principles have often been diagrammed on different axes, as the very idea of a two-by-two matrix is both easy to convey and helpful in solidifying strategies and innovations. I myself have been guilty of abusing this graphical tool to present proposals, analyse critical choices and, yes, even debate restaurant options with my friends. The truth is, once you get used to it, it really is an amazing resource.

Recently I had this idea of applying the concept to my roster of Commander decks, to help myself framing my deckbuilding choices and maybe understand what to bring at my local game store, at the next Grand Prix or at my friends’ kitchen table.

Adapting the Magic Quadrant for Commander

Commander is a format primarily devoted to fun. While it is nowhere near a non-competitive format, its multiplayer nature, its intrinsic randomness and the existing of the long-discussed Social Contract make it way more devoted to fun and enjoyment, rather than competition. To put things into perspective: many Commander playgroups promote a spirit of collaboration in deckbuilding and deck selection, as it is often customary to ask the whole table what they’d rather see played. On the other hand, I have never seen anyone approaching a Legacy Tournament asking their opponents what would be funnier to see at the table.

The strive for shared fun, of course, is not the only criterion determining the quality of the overall Commander experience. While making sure you are playing something funny for your opponents is certainly important, shuffling a deck you enjoy yourself is also crucial. In a perfect Commander world, we’d all play decks we truly enjoy and we’d only battle against decks we love seeing on the other side of the table.

There is probably at least a dozen additional perspectives to tackle when discussing Commander and I am sure many of them would be amazing subjects for future discussions, but let’s start from the very core of the format: fun. Fun for the player piloting the deck, as well as fun for the rest of the table. In other words: how consistently can each player define a vision they can enjoy for their deck? And how consistently does it impact on the rest of the playgroup?

In a way, this is not too different from Gartner Inc.’s perspective: a horizontal axis devoted to clarity of vision, which is in and on itself a relatively individual point of view, and a vertical axis focused on how this vision impacts the surrounding environment, in terms of execution and repercussion on the rest of the playgroup. Only this time, instead of whole companies, we can look at individual Commander decks within a player’s roster of available decks.

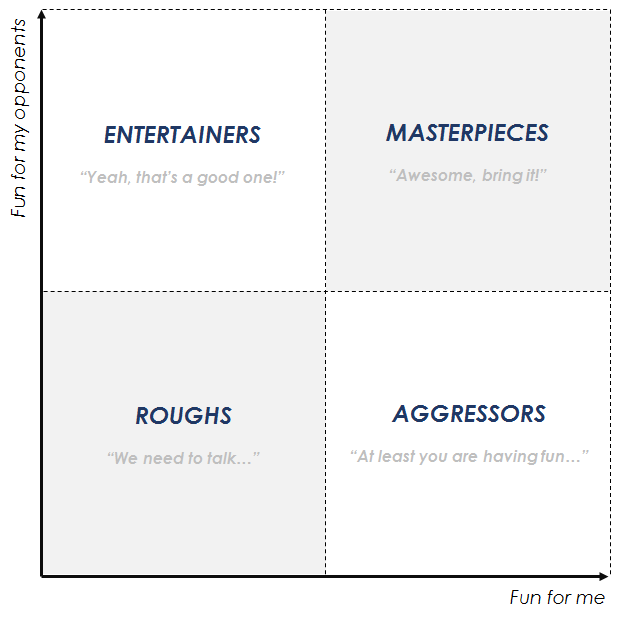

What I ended up with is the following two-by-two matrix.

Much like Gartner Inc.’s Magic Quadrant, we end up with a two-by-two matrix, aimed at mapping Commander decks within four areas:

- Masterpieces are the best of the breed; decks that are both funny for the piloting player and for the rest of the playgroup; they are always a welcome sight at the table and they embody the playgroup’s understanding of what Commander truly is; these can be the culmination of a process in which the whole playgroup learns to understand and respect everyone within it

- Aggressors can be the joy of their owner, but a pain for the rest of the tables; decks that are extremely competitive, or include many of the most frowned upon cards in the format can easily end in this category; when these decks show up at the table, they are often met with groans and complains, with their pilot grinning in evil content

- Entertainers are loved by the table, but are not equally enjoyed by player piloting them; either these decks are extremely non-competitive, or they are simply closer to the playgroup’s expectations, rather than their deck builder’s; they could have been built this way on purpose, or they can be a meeting point skewed in favour of the playgroup’s preferences

- Roughs are the most challenging decks to analyse; they may have been poorly conceived from the start, or maybe they are failed experiments, or they simply lost their charm over time, becoming way more repetitive than expected; another option is simply that, while being still good and playable, they are not as good and beloved as the other decks in the playgroup

Before we move forward, one thing must be mentioned. The Commander Magic Quadrant (CMQ) is not a Cartesian Coordinate System. Its axes do not necessarily go from zero to a maximum possible number, nor usually include negative values. Practically, this means that the centre of the CMQ is not some kind of perfect balance, nor the bottom left corner represents the absolute zero.

The best way to approach the CMQ is to view each item mapped in its areas based on the relative positions between one another. The positioning of each item is therefore not absolute, but can help understanding, within one or more player’s deck roster, how each fare against the others.

Let’s get in the details of this CMQ and understand how to approach it and what its main takeaways can be.

How can one measure fun?

Long story short: fun is unmeasurable. You could try and quantify the amount of endorphin and other substances released by your body when you have fun, but I’m not a doctor and, really, this is way out of my league. What you can do, is separately tackle each of the perspectives we discussed, not trying to measure them, but simply ranking the decks you are trying to map. In other words:

- Fun for me: try and rank your decks based purely on your personal enjoyment when you play them; forget your opponents, your win rate, the amount of money spent building it, the type of decks; write them down and, based purely on the amount of fun you usually have playing them, try and list them for the funniest to the least entertaining for you to play

- Fur for my opponents: what is your playgroup’s reaction when you bring a certain deck to the table? Do they groan or cheer? Do they smile or complain? Talk to your playgroup and ask them to rank your decks based on how much they enjoy playing against them

Once you have ranked all your decks based on your and your friends’ enjoyment, try and place them in the graph. Funniest for you go to the right, funniest for your playgroup on the top. Again, do not think absolutes, here, but try and distribute all your decks evenly along the two axes. Personally, this is what I ended up with, when I tried distributing my decks.

What really drew my attention, here, is the outliers that place themselves far from the centre of the CMQ. While some of these decks are relatively easy to understand, some may require a bit more context:

- My Diaochan, Artful Beauty deck is a pretty straightforward Wacky Chaos Commander deck, with a dense Red Planeswalker subtheme; it is one of the most welcome decks in my playgroup, as it is almost incapable of winning and it always provide some nice twist to traditional games; it fares very low in my personal enjoyment scale as many of its games are just auto-piloted by a number of random effects and the end result is kind of lacklustre

- My Kozilek, Butcher of Truth deck is almost the polar opposite: it’s a powerful one trick pony that plays amazingly, but it can be extremely oppressive to play against; meeting a hasty Eldrazi Titan on turn 3 is everything but a funny experience for my opponents and the sheer density of Mana Rocks usually means the deck’s plan feels very consistent and reliable – which is good for me, but not great for the players on the receiving end of an Annihilation 4 trigger

- The top positions are split between my Grimgrin, Corpse-Born and my Borborygmos Enraged decks; the two decks have been tuned after years of games and their playstyle is usually perceived as very non-oppressive, relying on anything but game breaking locks and hardly interactive combo

- The worst offenders are probably Saskia, the Unyielding and The Locust God; they are both extremely linear in their strategies, but turn out to be less consistent than Kozilek, while still being perceived as pretty non-interactive; the former can potentially take out a player within the first turns of the game, while the latter wins more via a single explosive turn, rather than after a long and well-fought battle

The easier takeaway from this exercise is that I can easily cherry pick what to bring at my local game store, balancing good and interactive games with the occasional nonsense we all need sometimes. This is a great starting point, but we’re barely scratching the surface.

So what is fun?

One thing that immediately comes to mind looking at this matrix is how much one person’s fun can relate to everyone else’s at the table. While the amount of available data is not sufficient to really plot a quantitative correlation, it is indeed possible to theorize some patterns based on one person’s character. In a way, we could easily diagram two perfect extremes in a Commander player’s personality.

To some players, fun is a zero-sum game. The amount of fun they are having is inversely proportional to the amount of fun everyone else is having. If they win, they usually do so by performing something extremely unfair within the game. Joy, to them, is an exclusively individual perspective and the fact that the opponents are having fun can actually be a detriment to their own enjoyment. To some extent, this is an extreme version of Spike from Magic’s personality traits. If they win and everyone else loses, they are happy. Any other scenario results in their discontent. Push it even further and they look like psychopaths who thrive in everyone else’s unease.

On the complete opposite of the spectrum, you have the perfect tablemate. This player’s fun is directly proportional to the amount of fun the whole table is having. Victory is irrelevant, with their only goal being the maximization of the enjoyment within the entire table. Think of these players as Group Hug players pushed to the extreme, to a point where everything they do is make sure everyone else is having fun. Winning a game is so low of a priority to them, that they genuinely never care about the outcome of a game. Again, the extremization of this profile is some kind of selflessness-devoted zealot who only aims at entertaining everyone.

Based on the way one may have plotted their own Commander decks on the CMQ, it is possible to theorize the personality of a player and their approach to the game. The more they approach the Spike curve, the more likely they are to adhere to the idea of a “pure” Spike player, hellbent on winning the game with complete disregard for the opponents’ entertainment. On the other side, the more players approach the Tablemate curve, the more likely they are to move towards a goal of maximized fun for the whole table, disregarding victory as a crucial factor in their own appreciation for the game.

Of course, every player is their own person and it is very likely that perfect adherence to a specific curve is never really achieved, unless the data available is extremely limited, skewing the plotting as a result.

What else there is?

Bridging outside of a single person’s Commander deck roster, two perspectives can be further analysed. First and foremost, comparing individual player’s CMQ can generate interesting comparison between members of a single playgroup, with some being more inclined to individual fun and others more prone to shared entertainment.

With some patience and a lot of effort by everyone involved, another perspective that can be approached is a collective effort within the whole playgroup to rank the entire roster of available Commander decks each player can bring to the table. Based on the size of your playgroup, this can really be a true feat of organizational skills and debate moderation, with the end result being a single shared vertical axis for the entire playgroup. As a result, instead of looking at individual placements of each deck, one could trace the average location of each player roster on the shared CMQ, tracing relative players’ profile and mindsets towards the format and the rest of their teammates.

I may be trying this out for a future update on the subject, so stay tuned if you’re interested.

One additional perspective that can be tackled, going back to an individual’s point of view and driving inspiration from Gartner Inc.’s Magic Quadrant, is a periodical re-assessment of a person’s CMQ. Our personal appreciation of our own Commander decks can really change over time, with new cards being released, new deckbuilding choices to explore and sometimes complete overhauls of existing strategies. While other constructed formats tend to focus on just fine tuning existing strategies, Commander has a way broader mindset and can really lead players to massive reinventions of existing decks or fanatic pursues of new approaches to revamp consolidated decks. I would personally like to revisit my own CMQ over time, especially to see If I managed to improve on the decks I have the least fine playing with and, on the other hand, If I can turn my more oppressive decks into better experiences for my playgroup. Should these be the only results, I’d say we’d already be on a great path of self-improvement.

One thought on “The Commander Magic Quadrant”