The Blind Eternities

The Blind Eternities are among the most interesting and fascinating “locations” within Magic’s Multiverse. As part of the game’s lore, the term Blind Eternities commonly refers to the space between Planes, a sort of chaotic zone existing between one world and another.

The Blind Eternities are universally described as dangerous, filled with powerful magic, aether and Mana that cannot be tamed by common wizards. This perilous area serves as a sort of connecting tissue between worlds and Planeswalkers are forced to traverse it to move between Planes.

As human being residing on Earth, we could be tempted to approach the concept of the Blind Eternities as our current understanding of outer space, though that would actually take us in the wrong direction. While outer space is largely devoid of life and almost completely empty, the Blind Eternities are full of energy and mysterious native beings of unconceivable nature.

Moreover, the twisted nature of the Blind Eternities makes it impossible to map them. While we, as a species, have spent a good portion of the past centuries mapping the known Universe, the Blind Eternities do not possess fixed points and coordinates to refer to. As a result, Planeswalkers can get lost in this unconceivable maze of pure chaos and most of them tend to remain in this space as least as possible.

On top of all this, common living beings are unable to access this well of chaos. And if they were, they would likely be distorted and annihilated by the unimaginable forces of this hostile environment. So, no attempt has ever been made to establish a permanent outpost, thus far.

The result feels somehow similar to Star Wars’ hyperspace, albeit with less known routes and way more chaotic entities residing within it. Think of Solo: A Star Wars Story’s depiction of the Kessel Run, but instead of a spaceship, you need a Spark to traverse it.

Not much else is known about the Blind Eternities, aside for the fact that the Eldrazi are native of this space, although we don’t know if they were spontaneously born here, if somebody created them or if they evolved to survive in this environment. It has however been confirmed that the Eldrazi Titans we have seen in card form on Zendikar and Innistrad are but manifestations of the true entities residing in the Blind Eternities. So, when you look at the card Emrakul, the Aeons Torn, you are actually looking at the entity’s presence on Zendikar and not at her true self.

The Eldrazi

Much like their presumed home, the Eldrazi are still largely a mystery. We do not know what they really want, why they consume and process worlds and what their role in the Multiverse is. Since their inception within Magic’s lore, they have been compared to similar beings within other fantasy and science fiction canons, although we don’t know enough of them to find a clear match.

For instance, the very title of Ulamog, the Ceaseless Hunger echoes Marvel’s Galactus and its constant need to consume worlds, while Kozilek, the Great Distortion’s mind-bending powers seem to call back to H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu. Add to this the fact that we know Emrakul is aware of her own existence and nature and she has proven to have a plan when she was imprisoned in the moon of Innistrad. So, they are anything but mindless monsters, although, again, we do not know what their ultimate goal is.

Truth been told, we do not even know if the three Eldrazi Titans are indeed separate entities or manifestations of the same collective being. Some have theorized that they could serve as forces of coerced evolution, consuming and reshaping worlds to propagate life throughout the Multiverse. According to this hypothesis, their version of life would be simply different from our understanding of it. Wastes, in the end, are not barren environments devoid of energy. They simply generate a form of Mana that is different than the one Planeswalkers are more familiar with.

Nevertheless, the Eldrazi are among the most fascinating entities in Magic’s lore, as they truly set themselves apart from the plethora of evil masterminds, brutal oppressors and “bad guys behind everything“, all too common tropes in modern fantasy and science fiction.

“Five requests I often have to ignore”

Despite many players’ fascination and curiosity towards the Blind Eternities and the Eldrazi, Mark Rosewater has recently ruled out the possibility of a Magic set taking place within the Blind Eternities themselves. More specifically, his explanation came as a direct response to Maria Bartholdi’s suggestion to explore more of this yet unseen environment.

Most of Rosewater’s reasoning behind this stance revolves around the fact that the Blind Eternities would feel too alien both for Wizards of the Coast’s Design Team and for the players themselves. The Design Team would be forced to play without core elements of Magic, such as the availability of five Basic Lands. Player’s expectations could also fail to be met, due to the lack of resonant elements most players are accustomed to in a Magic set. The Blind Eternities would shake the very fundamentals of players’ understanding of Magic and many would likely feel alienated by the end product.

The key aspect to remember, here, is that the Blind Eternities are not an environment like any other we have seen in the past. To put things into perspective: Phyrexia is a hostile environment of biomechanical abominations, but key elements like space, time, directions still exist. On the other hand, it is very likely that the very concept of above or after do not necessarily apply within the Blind Eternities, resulting in a chaotic and largely unrelateable setting.

Mark Rosewater’s reasoning is sound and understandable, but we may be missing a big opportunity, here.

The new big baddy

War of the Spark will likely culminate in the downfall of Nicol Bolas. I have shared my detailed predictions in a past article, but I think the majority of players would agree that the Elder Dragon’s downfall is now imminent. After years of scheming and plotting, players are justifiably lamenting some form of Bolas fatigue, so the time is probably ripe to pull the trigger on the character, whether permanently or not.

The obvious question, here, is: what’s next?

At the time of writing, we do not know what will come after War of the Spark and Magic’ Summer 2019 Core Set. A lot can be said about the need for a palate cleanser set, much like Kaladesh followed the full year of Eldrazi overdose we had with Battle for Zendikar and Shadows Over Innistrad. And then what?

Nicol Bolas has been presented as one of the most imposing and important characters in the Multiverse. With him out of the way, what would be a compelling new villain to propel future conflicts?

We already have a number of existing and known threats our main characters still need to deal with across the Multiverse. Heliod is still on Theros, alongside his unresolved business with Gideon Jura. The Raven Man is still shrouded in mystery and not much is known about its true identity and its goals, other than they somehow include Liliana Vess. Phyrexia as a faction is definitely on top of many players’ minds when it comes to iconic villains and unresolved narrative arcs. And at least one key character has expressed interest in returning to New Phyrexia to deal with the invaders.

The problem Magic is facing after Bolas’ defeat is how to follow up on his demise with a realistic, compelling and believable new threat. Interestingly, Magic is currently not alone in this.

Options from the Marvel Cinematic Universe

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is going to face a similar problem in the very near future, with Thanos, “the bad guy behind everything”, likely to face his defeat in the upcoming Avengers: Endgame. And then what? How do you top a now iconic villain? How do you build from there?

Introducing another arbitrarily powerful villain would likely result in most fans quickly losing interest. The Monster of the Week trope can work as an occasional divertissement, but having a powerful and iconic villain followed by a nearly identical powerful and iconic villain leads to a quick loss of interest among the fanbase.

One easy solution is to completely shift the paradigm. For the purposes of the MCU, instead of replacing Thanos with a new, equally imposing, equally powerful, equally cosmic villain, the story could now have our heroes face off against something completely different. So, no Annihilus and no Galactus.

Instead, I would expect the MCU to look elsewhere. The Skrull have been established as a unique faction and I would expect one of the upcoming sagas to revolve around the Secret Invasion arc. Or, with the likely introduction of time travel in Avengers: Endgame, the door could be open for Kang the Conqueror to make his debut in the MCU. The important thing is that the new villain or villains need to feel different and not a just rehashing of the same principle.

To provide an example of what I think you should try and not do, think about the DC Extended Universe (DCEU). Man of Steel introduce us to General Zod and, although the movie was far from good, the main villain had something interesting going on. Then almost all the following films had just nearly-identical undeveloped monstrosities as their main antagonists, from the incredibly powerful CGI monster that was Doomsday in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, to the incredibly powerful CGI monster that was Incubus in Suicide Squad, from the incredibly powerful CGI monster that was Ares in Wonder Woman to the incredibly powerful CGI monster that was Steppenwolf in Justice League.

When all villains feel somehow interchangeable, the stories blur together and the resulting experience feels very forgettable. If villains do not feel new, compelling and real, the entire story suffers. To quote Stephen King: “Monsters are real, and ghosts are real too. They live inside us, and sometimes, they win“.

Fortunately for them, Marvel and DC have decades of materials to pull from for their future cinematic endeavours. Magic, on the other hand, does not currently have such a long history of characters. Although the game is not without its iconic villains, it certainly does not have Marvel’s or DC’s plethora or characters. And many of the iconic villains established so far do not distance themselves enough from Bolas himself, in my opinion. The trope of “powerful and cunning bad guy with a mischievous plan” unfortunately applies to many Magic villains and most of them would not be able to fill Bolas’ shoes.

Much like the MCU, Magic is on the verge of dealing with one of its most iconic villains. So, if the MCU can easily turn to a very different type of new villain for its upcoming stories, Magic could take steps in the same direction.

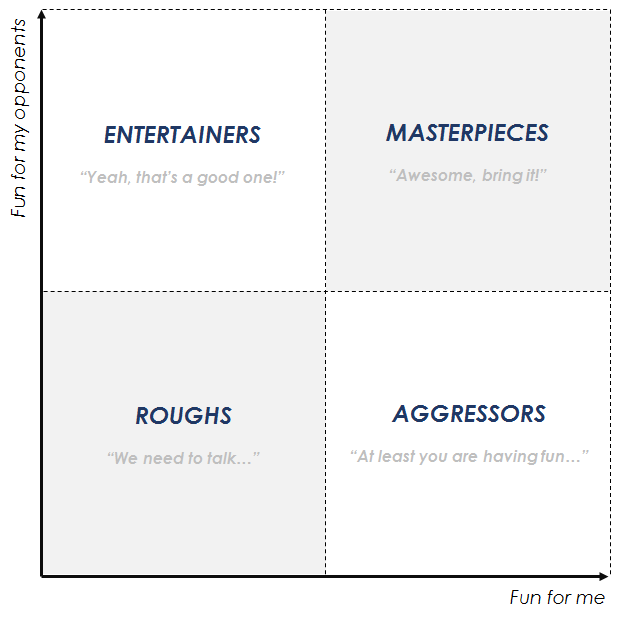

For example, Wizards of the Coast could consider introducing internal conflicts within the roster of main characters, with or without an external force infiltrating the main team of heroes. For instance, we could envision an equivalent of Marvel’s Avengers Disassembled narrative arc, with the story focusing on the disbanding of the Gatewatch and the resulting conflicts between former allies.

Another option would be to revisit the concept of time travel in Magic, as the last iteration of this concept came with the Tarkir block. Oddly enough, despite this being an almost unprecedented feat in Magic’s story, the repercussions of Sarkhan‘s time travel have limited effects on the Multiverse. Sure, the timeline of the Plane was drastically altered, affecting most Tarkir-bound characters, but most of the other Planeswalkers seemed to hardly notice the change.

Revisiting time travel would pose an interesting challenge to Magic’s heroes, as the Gatewatch has not dealt with time travellers, yet. And let’s not forget Emrakul is still trapped in the moon of Innistrad. A moon conspicuously made of silver, the only material in Magic’s lore that can travel through time.

A Blind Eternities proposal

Taking into consideration Mark Rosewater’s comment on the unlikeliness of a Magic set taking place within the Blind Eternities, I think we can still work towards a compromise. Let’s keep in mind that:

- The Emrakul storyline still needs to find some kind of resolution

- We need something new and different to come after Bolas’ long arc

- The Blind Eternities are a still unexplored setting that fans have often asked about

What if one of the upcoming stories revolved around a Plane breaking into the Blind Eternities? We are no strangers to world-ending threats in the Multiverse, but what if, this time, it was not happening at the hands of a powerful villain, but simply as an occurring phenomenon?

Or, if Wizards wanted to provide a single source of this event, what if this was the by-product of Emrakul being trapped into Innistrad’s moon? What if she was calling upon the Blind Eternities themselves onto Innistrad, from within her cage? And what if she was also doing so across time, ideally summoning towards herself even the other two Eldrazi Titans, which the Gatewatch thought defeated?

This would result in an admittedly challenging storyline to pull off, but it would allow to:

- Complete or at least progress the Emrakul storyline – ideally with the main characters forced to release her from her prison and set her free again throughout the Blind Eternities, potentially accompanied by the time-shifted Eldrazi Titans

- Introduce a narrative arc where the main opposing force is a slumbering, almost unwilling entity and not a present evil mastermind – again, carrying a strong Cthulhu vibe and not simply reiterating the concept of a mastermind villain setting a complex plan in motion

- Depict the Blind Eternities as a portion of the whole worldbuilding – most notably the portion of Innistrad shifting into the space between worlds, while the remainder of the set still features typical Magic elements

The (colourless) opportunity

Setting aside Magic’s lore, I think it is worth mentioning that colourless Mana as a concept has recently seen a resurgence in popularity, especially in an open-ended and casual format like Commander. At the time of writing, the latest episode of Game Knights by the Commander Zone has marked the first appearance on the show of a fully colourless deck, piloted by Ashlen Rose. Her deck was also the subject of a dedicated episode of the same podcast, which helped popularizing colourless as a valid deckbuilding option for Commander players.

On top of that, we have never had a single colourless preconstructed deck in any of the Commander supplementary products. As I have already mentioned, I fully expect this year’s Commander supplementary product to mark the first time a colourless preconstructed deck is presented to the players.

The sensibility of casual players towards colourless is recently increasing, while support towards this archetype is still minimal. While it certainly wouldn’t make sense for Wizards of the Coast to cobble together a set just to ride a fairly localized trend, there is a number of elements pointing towards the big opportunity that a Blind Eternities set would present.

Moreover, if the four consecutive sets of Battle for Zendikar and Shadows Over Innistrad led to a justifiable Eldrazi fatigue, having a single episodic set taking place between Innistrad and the Blind Eternities would probably be an interesting divertissement before or after a larger storyline.

Considering War of the Spark is likely going to close Nicol Bolas‘ narrative arc and assuming this summer’s Magic Core Set is not going to introduce major shakeups in the current storyline, I would expect the following set to take us somewhere new, after a full year of Ravnica-bound storylines. Then we may be off to New Phyrexia or Theros, where unresolved plots still demand our heroes’ attention, or we may be taking a much-anticipated detour to Lorwyn.

Between these future – and yet pre-established – plots, I strongly believe we have the opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: advancing or resolving Emrakul‘s storyline and introduce Magic players to the unfathomable well of creativity that are the Blind Eternities.